It may surprise you that, despite our seemingly vast knowledge of the human body, we’re still decently in the dark when it comes to the smaller portions of the cardiovascular system. Even more surprising, the answer to that problem isn’t lying in more powerful microscopes. It’s in a heart pumping pure, shiny liquid metal.

Until now, modern imaging techniques have given us a fantastic understanding of the heart’s larger blood vessels, but they’ve done little to give us a clear view of the innumerable smaller branches these vessels break into. As we stand today, one of the most widely used imaging methods involves filling the vessels with a contrast agent (typically iodine) that absorbs x-rays more than the tissue around it, resulting in an image in which the vessels themselves are very much apparent; the denser the contrast agent, the clearer the image. The only problem is that our current contrast agents carried a pretty limited rate of x-ray absorption — until now, that is.

Researchers at Tsinghua University in Beijing have taken a potentially wildly complicated problem and come up with a (relatively) simple solution by injecting the heart with gallium, a chemically stable metal that melts at about 85 degrees Fahrenheit. In other words, it has no problems flowing through the labyrinthine vessels of the heart.

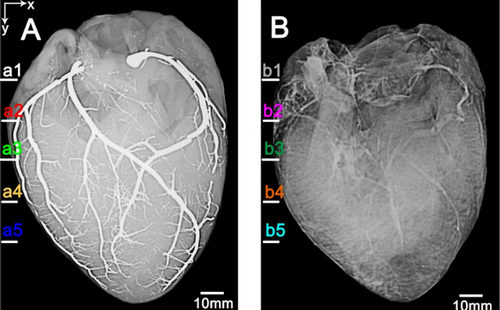

And as the top image (which show a pig’s heart injected with gallium on the left and iodine on the right) prove, we are well on our way to a far great understanding of the heart than we’ve ever had before. The technique was even able to display capillaries a mere .07 millimeters in diameter. Plus, since cooling the metal will freeze it, there’s even the opportunity to create anatomically precise moulds that display the structure in 3D.

The next step will be human trials, and the research team is even optimistic that the technique could be used to image actual living human tissue. As Physics arXiv Blog explains:

They point out that gallium is chemically inert and believed to be non-toxic in humans. And they say a small amount of the metal can be injected into the target vessels and sucked out afterwards without leaving a residue.

Of course, getting to that point will take years of research and precautions. But if the scientists’ optimism is anything to go by, gallium-pumping hearts may have the potential revolutionise our understanding of our very own selves.

ASHLEY FEINBERG